Twelve miles separate the Canadian border and the frozen parking lot of St. Lawrence University, where the most talented offensive mind in college basketball is currently stuck. It’s January 2003, and the sub-zero temperatures of Canton, New York—the town averaged a low of -5.4 degrees that month—somehow bite even harder inside Nevada Smith’s 1993 Dodge Ram van. The light brown clunker is well-known around the town of 6,000 for its orange shag carpet interior and LED lights along the floor. It’s also known—more importantly at this moment—for its inability to run longer than 5 minutes in the winter.

What St. Lawrence’s newest graduate assistant lacks for in understanding about carburetors and transmissions, he more than makes up for in ball screens and transition offenses. His concepts are brash—and borderline maniacal in a year when Division I programs average 69.8 points and 6.2 threes per game—but Smith sees the game differently. He knows what these forward-thinking sets and reads can produce when implemented with the right group of players. It’s going to be the next evolution of basketball.

That evolution will need to wait about 20 more minutes until the van that fellow coaches have coined the “Mystery Machine” is thawed out and ready to run again. He’ll get it fixed soon, and the mechanic who inspects it will laugh, telling him “this van is built for Florida, and you’re in the coldest place in the world.” So the 22-year-old Smith bundles up and waits for his next move.

His first few months on the job have been difficult. The Pennsylvania native is just months removed from college graduation. As life in Division III basketball tends to require, Smith is essentially the Saints’ lead assistant, manager, video coordinator, academic advisor, and top recruiter—all while working toward the master’s degree that he promised his uncle he would earn.

He tries the ignition again. Success. He doesn’t know it at the time, but as Smith pulls out of the parking lot and heads back to the apartment he shares with three football assistants—where the pipes freeze in the winter so showers are off-limits, and the four huddle around a space heater to watch games at night—this blossoming basketball technician is embarking on a fascinating coaching journey—one that will soon run opposing defenses out of the gym.

“My whole life,” says the 43-year-old Smith, now the lead assistant and offensive coordinator of the title-contending Marquette Golden Eagles, “has been to adapt with what you’ve got and figure it out.”

Brian Murphy traded in Southern California beaches for the northern panhandle of West Virginia in 2001. Accepting an assistant role at Bethany College under Rob Clune gave him a two-fold opportunity: earn a master’s degree while implementing progressive, if not radical, offensive philosophies he found success with at Pomona-Fitzer under the legendary Charlie Katsiaficas.

He figured the offense could work thanks to a handful of talented scorers that Bethany had returning—including an undersized shooting guard who wasn’t exactly lacking in confidence.

“The first day I met Nevada Smith,” Murphy said, “he told me he was the best shooter in the country.”

Bethany, West Virginia was home to 234 residents when Smith arrived two years earlier. The 6-foot-1 guard had matching scars on each knee from ACL tears suffered his sophomore and junior seasons at Kiski Area High School, where he was known for his bounce and—he swears—his defense. Bethany featured one bar (Bubba’s)—more than the combined number of stop lights and gas stations in the one-half square mile town—and a Division III basketball team coming off the worst season (3-22) in its 92-year history.

Smith knew playing time would be available, and it helped that Bethany offered sports management as a major—his dream was to attend law school and become a sports agent. Smith committed to Clune that summer (the Bison won one of their three games during his official visit) and hit the ground running.

The wiry freshman with sideburns and frosted blond tips made an immediate impact in practice, moving flawlessly without the ball to find open spots for jumpers. He had in-the-gym range, burying triples from well beyond the 3-point line each time he took the floor.

“The kid was automatic,” said Keith Schubert, a fellow 1998 recruit who eventually became the school’s all-time leading scorer. “It was an everyday occurrence with him.”

Clune started Smith along with three other freshmen, “improving” to five wins in 1999. Led by that budding sophomore class, the Bison won nine games in 2000, with Smith connecting on 46% of his triples as a second-year starter. But it was Murphy’s arrival in 2001 that flipped a switch about the way Smith approached the game.

“He changed the way I think about basketball,” Smith says. “He changed everything.”

Bethany subbed out the Princeton offense for a more free-flowing, screen-heavy offense that predicated itself on getting the ball in its best players’ hands as often as possible. After topping 80 points twice in 25 games the previous season, Murphy’s offense scored 90+ in four of their first 10 games, all wins. That momentum carried on throughout the year, with the Bison finishing 16-10 and earning the program’s first conference title in nearly 20 years.

A major part of that success? Smith, the self-proclaimed “best shooter in the country,” speaking his confidence into existence. He was a self-taught gym rat all summer as the new offense took shape—it doubled as an always-welcomed excuse to skip the weight room—and constantly watched film with Clune. It paid off. Smith opened the season 7-for-8 from deep—and never looked back.

His junior season, Smith earned All-PAC First Team honors by leading all of Division III in 3-point makes (101) and finishing fifth in the country in 3-point field goal percentage (49.5%). Those 3s broke a seven-year stretch in which a Grinnell player had led D-III in makes, and the four players ahead of Smith in percentage averaged 122.2 attempts compared to his 204.

“Teams knew he could shoot and he kept draining them anyway. It was amazing,” Clune said. “He’d frustrate the hell out of defenses.”

Bethany’s sharpshooter made 109 more 3-pointers as a senior (fifth in Division III) and the Bison steamrolled their way to a 21-8 record, winning another PAC title and advancing to the second round of the Division III NCAA Tournament—losing to eventual national champion Otterbein.

“Nevada never took a bad shot,” Schubert said. “He was always calculated.”

Smith’s dream season included a few school records—but leading the country in free-throw percentage was dashed—by a lane violation. Smith stepped to the line late in the season for a 1-and-1 in the closing seconds of a blowout win—he didn’t earn many shooting fouls but was the go-to recipient of inbounds plays when teams were trailing and forced to foul. He calmly splashed the net—except it didn’t count. “Big Pete” Stokic, a Yugoslavian center who was more body than basketball, had stepped in early.

Wave off the free throw.

By season’s end, Smith finished one free throw attempt shy of qualifying for the record (67 of 72), and his 93.5% mark would have topped Suffolk guard’s Jason Luisi’s by a full percentage point.

“From that point on, I was like, ‘I don’t want anybody in when I’m shooting. You don’t need to put anybody in. I’m not missing,’” Smith said, (now) with a laugh. “‘Get out of here. You’re not getting a rebound.’”

He may not have the 2002 Division III free-throw title, but his 313 career 3-pointers and 87% clip from the foul line still stand as Bethany records. Even still, his most impressive shooting performance came a few months after graduation.

Murphy had accepted a job at Loyola University in Baltimore after finishing his master’s at Bethany and held an annual shooting clinic for 150 local high-school hoopers each summer. Smith attended as an onlooker in support, sitting atop the bleachers in flip-flops and sweatpants. Midway through the clinic, Murphy was driving home a point on a specific shooting drill when he pointed up the bleachers, singling out Smith.

“And that guy,” Murphy told the players, “is the best shooter in the country.”

Heads turned. Eyes rolled. A few players chuckled.

So Murphy made a bet with his camp: That guy is going to come down here and shoot 20 3-pointers. If you think he’ll make 18 or more, stand on that side. If you think he makes fewer than 18, stand on this side. Losers run.

Smith came off the bleachers and flip-flopped his way to the top of the key.

He made 10 of his attempts. Before he missed. Then he buried nine more in a row.

All but four campers ran as Smith and his 95% performance laughed from the sidelines.

“The biggest thing with shooters is confidence, and Nevada wasn’t lacking anything,” Murphy said. “I’d take him over anybody, still today.”

Ithaca College head coach Jim Mullins was working in his office in the summer of 2006 when his phone rang.

“I’ve got your new assistant coach,” said the person on the other end of the line.

It was Sherry Dobbs, an assistant at nearby Podstam who frequently combined resources—namely a Chrysler P.T. Cruiser with 90,000+ miles on it—with Smith on recruiting trips to New York City and New Jersey. Those 6-hour drives from Upstate New York left plenty of time for casual chalk talk, and Dobbs understood quickly that the St. Lawrence graduate assistant was a gifted basketball mind in the making.

2-for-1s at the end of halves. Double ball screens on the wing. Shooters in the corners.

Commonplace now. Unheard of then.

“He was just looking at things from such a different level than a lot of us,” Dobbs said.

Mullins did his due diligence beyond Dobbs’ recommendation and heard nothing but effusive praise for Smith, who after graduating from St. Lawrence became a 24-year-old head coach at SUNY-Canton for a season and then latched on with Allegheny College in 2006 under Clune, his old college coach.

The Ithaca fit couldn’t have been better. Mullins was known in the upstate New York hoops community as a true coach’s coach. Twenty-plus years of head-coaching experience speaks for itself, but he isn’t afraid to let his assistants run their stuff—once they’ve got their feet wet.

When Smith arrived, Ithaca was running the Swing offense, a methodical, repetitive motion that involved ball reversals and post-ups—typically eating up clock in the process.

“I couldn’t stand it,” Smith admitted.

Heading into Year 2, Mullins let Smith know that the offense was his—and it didn’t take long for the excited young assistant to knock on the head coach’s office door with film and notes that summer.

“Look at this offense,” Smith told Mullins. “This is what the Phoenix Suns are running.”

Mike D’Antoni’s Phoenix Suns had just ripped off 54 and 61 regular-season wins behind their Seven Seconds or Less offense that led the NBA in offensive rating, effective field goal percentage, assist rate, as well as 3-point makes, attempts, and percentage in both the 2006 and 2007 seasons. The offense was unlike anything the league—or any level of basketball—had ever seen, led by All-Stars Amare Stoudemire and Shawn Marion…and the reigning NBA MVP.

“The Phoenix Suns have Steve Nash,” an apprehensive Mullins reminded Smith.

“But we,” Smith replied, “have the Division III Steve Nash.”

Sean Burton had started each of his first two seasons at Ithaca, averaging 12.8 points and 4.1 assists while earning first-team all-conference honors as a sophomore. The potential was there for the 5-foot-9 point guard, and a slew of cerebral shooters—not too different from Smith’s own scouting report—made it a perfect fit.

Earlier that summer, Smith had reached out to Vance Wahlberg, a basketball innovator whose dribble-drive offense was constantly topping 100+ points at Fresno City College. Wahlberg had just become the head coach at Pepperdine, and he’d later join John Calipari’s UMass staff before NBA stints with the Nuggets, Sixers, and Kings.

Smith’s idea to replace the Swing? A dribble-drive offense with ball-screen starters that mixed in some of the Horns action the Suns were making famous.

“When he came up with something, it wasn’t just because he read about it or liked it. He did it aimed at our personnel,” Mullins said. “But holy mackerel, it was good stuff. After a year, it just became very evident to me that he was thinking on a different plane. He was playing chess.”

With the Swing out and Smith in, the Bombers, well, started bombing. Led by “the Division III Steve Nash,” Ithaca averaged 85.5 points on more than 26 attempts from deep over the next two seasons. Smith’s offense topped 100 points nine times in that span—something the program hadn’t done once since 1991.

Burton became Ithaca’s first All-American since 2000 and the first back-to-back recipient in nearly two decades. In his final two seasons in Smith’s offense, he led the country in assists and was fifth in scoring.

The Bombers hit the century mark seven more times between 2011 and 2012, averaging 84.4 points. Leading the way was Sean Rossi, a Smith recruit who ultimately became the all-time assist leader in Division III history (957) and another All-American.

The offense wasn’t a gimmick, either: The Bombers went 81-27, the best four-year stretch in the program’s 94-year history, winning three Empire 8 conference titles and earning a pair of Division III NCAA Tournament appearances.

“Playing in his offense,” Rossi said, “was like having the answers to the test before you took it.”

Opponents tried everything—literally. McGuiness, Smith’s close friend who captained the Bethany teams the two played on together in college, was the head coach at conference foe Hartwick at the time. He also doubled as the school’s facilities director, and when Ithaca came to town every other year, he swapped out the nets in the main gym for new, stiffer ones in an attempt to slow down the Bombers offense. The results against Smith’s offense? Losses of 12 and 22 points. Ithaca averaged 86.5 points in the wins.

“You needed something to slow them down. We played fast and liked to get out and run. But [against Ithaca], we knew we had to slow this thing down or we’re not going to win,” McGuiness says. “If we try to get 100, they’re going to get 120.”

Defenses deployed intricate denial tactics, wove in schemes they had previously never tried, and went as far as stalling (Ithaca won that one by 28 despite being “held” to 64 points on 65% shooting). Time and time again, defenses did what they could—and Smith’s offense always had an answer.

“Some of the stuff he came up with,” Mullins said, “was the best stuff I had ever seen.”

Smith found his groove in those five seasons. He golfed every day (playing off scratch, nonetheless) and taught golf classes, surely letting his students know that he captained the men’s golf team at Bethany for three years and earned All-PAC Second Team honors as a junior. He let it fly from deep in multiple summer basketball leagues in Syracuse, doubled as an assistant on the women’s softball team, and was unofficially the youngest member of Ithaca’s Elks Club chapter.

Ithaca wasn’t a place people left. When you found that groove, you stayed. But when the opportunity presented itself for Smith to continue expanding his offensive philosophies as his own boss, he took a 100-mile journey south—one that might as well have required a time machine.

When 31-year-old newly appointed head coach Nevada Smith traveled in the fall of 2011 to La Plume, Pa.—population of 844, located about 20 minutes north of Scranton—and walked into Keystone College’s Gambal Athletic Center, something caught his eye. Hanging from the ceiling on the sides of the gym were four wooden backboards, painted white, with no inner squares. Had it not been for the orange double rims bolted on, there would have been no resemblance to anything basketball-related.

The visitor’s bleachers were five rows deep—it was a coin flip most gamedays whether they’d fully extend out—and players were told to avoid dunking too hard on the rock-solid rims to save their wrists. Court time would be limited with the school’s other fall and winter teams also needing to practice inside the gym.

“It was Hoosiers in 2011,” said point guard Dan Candemeres, who arrived as a freshman at Keystone that same fall.

It wasn’t his first head coaching gig—his SUNY-Canton Aggies went 7-17 in his lone year there. But he arrived that year as a more seasoned coach with a better frame of mind, five years of successful offenses, and a roadmap for success.

He drove 90 minutes to meet with his team for the first time, just two weeks before the season began. The offensive guru had his computer with him, stuffed with game film, PowerPoints that listed team expectations, and notes on how his offense would run. When he arrived for the 6 p.m. meeting, he realized he hadn’t received any keys—and all the doors to the classrooms were locked.

Adapt with what you’ve got and figure it out.

“We sat in a circle in the lobby of the gym and had that first meeting,” Smith said. “We just talked.”

Smith’s message to his team in that circle was clear: We’re going to get up and down, we’re going to outwork teams, we’re going to make defenses adjust to us, and we’re going to lead Division III in scoring.

Assistant coach Brad Cooper heard that message loud and clear. Smith’s first Keystone hire, Cooper had just completed his graduate assistant work at Fredonia State, a team that went 6-18 and averaged 57 points with a more traditional halfcourt, back-to-the-basket offense.

“I learned on the first day of practice,” Cooper said, “how fast everything was going to be.”

The Giants scored 95 points in their second game while hoisting 39 triples and making 55% of their 2-pointers in a win. Candemeres, who described himself as a “walk-it-up-the-floor point guard” in high school, finished with 23 points, attempted 14 3-pointers, and handed out five assists.

That team finished 21-6, with three of those losses coming against an eventual 31-2 Cabrini College team that made the D-III National Championship. The Giants settled for fifth in the country in scoring (90.1 points), and ranked nationally in field goal percentage (29th), 3-pointers (12th), assists (14th), and assist-to-turnover ratio (6th).

“It was just this feeling of walking into games knowing we were going to win,” said Candemeres, who went on to finish his Keystone career ranked in the top-6 all-time in points, 3-pointers, and assists. “I never had that until I played for Nevada.”

The Giants went 18-10 the following season behind another dynamic offense that averaged 84 points, 10 triples, and 17 assists per game—all top-8 marks in Division III. Though they lost in the CSAC conference title games in consecutive years, the offense was electric: In two seasons, Keystone attempted 1,570 3-pointers—500 more than its opponents—and lived at the rim, shooting 56% from inside the arc.

“Nevada was very humble and quiet, but you could tell he had a thorough plan. He never seemed unsure of himself,” Cooper said. “He had an absolute answer for any type of coverage on any action.”

Those results stemmed in part from Smith and Cooper living together that second season. The apartment they shared resembled the basketball version of a mad scientist’s laboratory: A whiteboard in the living room for diagramming plays. Notes sprawled on anything from computer paper to napkins. An NBA game on the TV whenever possible. The self-proclaimed “basketball junkies” picked each other’s brains, ran through hypotheticals, and waxed poetically about the future.

“We would just be talking and watching ball. It’d be all night, just writing on napkins, talking outside the box with different ideas and philosophies,” said Cooper, now an assistant coach at Hamilton College. “I’m always trying to bring something unique to the table now, and a lot of that came from Nevada.”

Though it wasn’t the Bad News Bears by any stretch, Smith’s accomplishments were still notable given the state of Keystone College. Recruiting to a small school with few resources and fewer glass backboards was tough enough, and it didn’t help that nearby schools like Scranton, King’s, and Wilkes all had more to offer in each of those departments.

“I’m watching them play from afar,” Dobbs recalled, “and I’m like, ‘How is he getting these kids to win 19 and 20 games there?’”

Dobbs wasn’t the only one paying attention to Keystone’s high-octane offense. And that’s when a call from the Houston Rockets came in.

Daryl Morey had considered, interviewed, or vetted around 80 candidates for the Rockets’ D-League head coaching vacancy in the fall of 2013—and none of them fit the mold. That is, until he and the Houston brass stumbled upon numbers from a small basketball school in La Plume, Pa.

Some 1,600 miles away, Nevada Smith was getting a practice plan ready for the start of his third season at Keystone College. He can count on one hand the number of times he looked at his office phone in two seasons—but that morning, he noticed a voicemail in his inbox.

It was Jimmy Paulus, a scout for the Houston Rockets. He loved the offense Smith was running and wanted to interview him for the opening in Rio Grande. The Rockets were undergoing an offensive transformation from beyond the arc of their own—and needed a coach to match those philosophies. Smith fit the bill.

Smith’s first thought? “Hmm, that’s different.” His first reaction? To pick up his cell phone and text his friend group: “Who’s messing with me?”

The likely culprit was McGuiness, always the prankster and someone with ties to Paulus. When he and the rest of the chat texted back that none of them would have gone that far, Smith dug in.

It really was Paulus on the other end, and the Rockets really were interested in Smith heading up the franchise’s D-League (now G-League) roster. The first call with Paulus went well enough that Morey hopped on the phone for a follow-up—and then invited Smith to fly to Houston for an in-person interview.

“It was the most fun interview I’ve ever had,” Smith said. “It was so laid back. I was just having fun with it. If I didn’t get the job, who cares?”

Smith met Morey in Houston in a room that also included Chris Finch, Kelvin Sampson, Gianluca Pascucci, BJ Johnson, and Monty McNair—a laundry list of top basketball minds. The group fired off questions about basketball philosophy, talked X’s and O’s, and watched Keystone film from the previous year—including a seemingly low-percentage play in which Keystone guard Tim Benedix fired a deep 3 early in the shot clock.

“Do you like that shot?” Morey asked in a condescending tone—trying to bait Smith.

“Yeah, I do,” Smith replied. “That kid’s our best shooter, and it’s really hard for him to get to the line. Deeper threes are open because teams don’t think you’re going to take them.”

“That was the moment he was hooked,” Smith said.

He was offered the job two weeks before the season began and accepted without hesitation. Smith informed his Keystone team and coaching staff—Cooper took over, a position he held through the 2022 season—and got to work.

Smith had a two-week incubation period where he met regularly with Finch and Sampson to learn new terminology and understand the strengths of his new roster, packed with talent he had never seen before: “The worst kid at our tryout was the best kid I had ever coached,” he said.

It also gave him time to lean into the one goal Morey had set for him: be the highest-scoring, most efficient team in the league.

The Vipers ripped off nine wins to begin the season with an offense that wouldn’t slow down—RGV averaged 129.4 points in that stretch, including games of 133, 139, 145, and 153 points. That juggernaut of an offense—which included future NBA’ers Robert Covington and Isaiah Canaan—went 29-20 and led the league in offensive efficiency (114.6). The Vipers attempted 45.4 3-pointers, nearly 10 more than any other team. They fell to second in efficiency in 2015—that squad included Clint Capela—but when Houston fired Kevin McHale following a five-game loss in the Western Conference Finals to Steph Curry and the Warriors, Morey’s house-cleaning included the entire Rio Grande Valley staff.

Fourteen years of offensive creativity and ingenuity established Smith as a brilliant engineer, but a meeting in the spring of 2016 brought a new facet of his coaching career into view: Culture.

Smith was introduced to Erik Spoelstra through then-Miami Heat beat reporter Tom Haberstroh, whose good friend Pete Friedland played at Ithaca. Though there weren’t any job openings in South Beach that fall, Spoelstra used Smith as an offensive consultant in 2016—leading him to accept the head coach position with their Sioux Falls G-League affiliate in 2017.

“It was the first real job where culture was a big talking point. I had never done anything like that before,” Smith said. “Up until that point in my life, it was always about getting the best players you could. It changed my whole philosophy on basketball.”

“Heat Culture” meant playing with a certain toughness and ferocity. It also meant talking about more than just basketball—with the staff making an effort to understand how players were doing mentally and making sure teammates got along together.

Smith’s instructions were to spend 75% of the time on defense, yet his offenses ranked in the top-10 in offensive efficiency in all three seasons. He helped develop NBA talent in Duncan Robinson, Malik Beasley, and Derrick Jones Jr., compiling a 78-72 record.

But the catch-22 of the G-League began to catch up with Smith after five seasons. Sustained success is only possible with roster continuity, which is only possible if you aren’t accomplishing your main goal of graduating players to the NBA roster.

“It was so transactional. We’d always get pretty good and then lose everybody,” Smith said. “The D-League at that time, there was no depth. When you lost players, you’re pulling guys off the waiver wire who haven’t touched a basketball in a month.”

Though he admits the jump to the NBA was the best thing to ever happen to him, Smith always knew a path back to college basketball was inevitable. Mark Daigneault, then the head coach of the Thunder’s G-League affiliate, had the same sense that Smith was looking to get back into the college game. That’s when he told him there was a coach in Austin, Texas that Smith should get in touch with.

Shaka Smart began his coaching career at California University of Pennsylvania in 1999, about 50 miles east from where Nevada Smith was ripping through nets at Bethany College. While the two never overlapped, Smith does remember hearing Smart’s name after the latter recruited one of the former’s high school teammates, Matt Molinaro, to Cal PA.

Smith was a casualty in another round of NBA house-cleaning late in the summer of 2019—which meant most collegiate bench spots were accounted for. Smith shot Smart a quick text letting him know he was looking to get back into the college game—and though Smart told him he appreciated the interest, there weren’t any openings in Austin.

But a spot opened up in Austin prior to the 2020-21 season after assistant Luke Yaklich accepted the job at University of Illinois-Chicago. And Smith was surprised to get a call back from Smart.

“He got back to me,” Smith said. “That’s a testament to who Shaka is.”

The two talked a little hoops and a lot of culture. Smith naturally loved Smart’s Division III background as a player at Kenyon College and his grad assistant work at Division II Cal PA. He was also impressed with how much Smart reminded him of Spoelstra. Phone calls became Zoom calls, and it wasn’t a difficult decision for Smith to accept when Smart offered him a role as the Longhorns’ director of player development prior to the 2020-21 season.

“I just wanted to work with someone who was a good person and did things the right way,” Smith said. “He could have offered me any position with any salary, and I was going to say yes.”

The timing couldn’t have been better from a player personnel standpoint. Smith implemented some more spacing on the perimeter and ball screen actions with three bigs—Kai Jones, Greg Brown, and Jericho Sims—who each became NBA draft picks the following June. The Longhorns were the heaviest pick-and-roll team in the country and saw their offensive efficiency jump into the top-25 in Smith’s first season.

Though the Longhorns won 19 games and the Big 12 Tournament that year, a last-second loss to 14-seed Abilene Christian in the opening round of March Madness put the writing on the wall for Smart and his staff. No tournament wins in five seasons at a school craving trophies meant that, despite the foundation the staff was building, a fresh start somewhere else was inevitable.

That new beginning came in Milwaukee. And two weeks after Smart became the 18th head coach in program history—bringing with him Smith and a handful of others from Texas—the staff received a commitment from Tyler Kolek.

Point guards have always been at the core of Smith-led offenses, each with different skill sets: Burton was a scorer. Rossi was a passer. Candemeres was essentially a shooting guard. D-League guards knew how to play fast. Texas’ Matt Coleman was lightning quick and great in the paint. All different in their own right, but all possessed the common ability to manipulate the defense, something Smith said is a lead guard’s most important attribute.

All bought into what Smith was selling, and the results spoke volumes. But…

“If you had a factory to create a Nevada Smith point guard, it would spit out Tyler Kolek,” Candemeres said.

“He’s right,” Smith said upon hearing that quote.

Kolek has been the anchor of two dynamic Marquette offenses—but he didn’t get there on his own. Ask Smith about his proudest coaching moment—from St. Lawrence to Marquette—and he’ll immediately mention getting players to buy in. No one has done that better than Kolek.

The two sat down following Kolek’s first season and looked at the shooting numbers—it wasn’t pretty: 32% from the field—including just 42% at the rim—and 28% from deep. Originally recruited as a lead scorer, Kolek naturally found himself with the ball in his hands and was blossoming into a gifted distributor (5.9 assists) in Smith’s offense. With some diligent offseason work and a few tweaks to his shot, Smith and the staff saw unlimited potential.

That offseason paid off—and then some. Kolek exploded in his second season at Marquette, improving his 3-point shooting to 39.5% while finishing 59% of his attempts at the rim—all while leading the Big East in assists and points created on his way to an All-American season.

The pair made a few small tweaks again this past offseason, extending Kolek’s range and working on making his shot more of a single fluid motion. Through 14 games, Kolek is shooting 42% from deep. He’s making 65% of his shots at the rim, and his true shooting percentage (63.9%) is third best in the Big East among guards, more than 20% points higher than his sophomore season (43.7%)—all while conducting Marquette’s high-octane offense as the most gifted passer in college basketball.

“Right from the jump, [Nevada] empowered me to do what I do,” Kolek said. “It’s been a great marriage—not only him, but Coach Smart as well. Nevada just gives me the ultimate confidence to be who I am, and that’s why it works so well.”

Smith has earned the trust of his players—they’ve heard stories of his shooting prowess in West Virginia and see it in action at times in practice. It matches the trust he’s earned from the head coach. Smith knows he can come to Smart with new concepts (and often does) and will be heard as long as he’s got rationale for the ideas. Nothing is off-limits between the two—disagreements happen but are always constructive—and that balance has struck a remarkable chord between two of the game’s brightest minds.

“[Nevada’s] phenomenal,” Smart said. “I appreciate him because he balances out my craziness sometimes, and he never really judges me for it. He has a humility but also sturdiness to him that makes him really special for us.”

Smart has been a Division I head coach since 2009. Before hiring Smith, his VCU and Texas offenses finished in the top-25 twice (2009 and 2013) in an 11-year span. Since Smith joined his staff, Smart-led teams have finished in the top-25 twice in three seasons and are on pace to do it a third time in 2024.

Though Smith has graduated to lead assistant and coordinates the offense, he is continually impressed with Smart’s knack for taking concepts and ideas talked about in offensive meetings and relaying them verbatim to the team. Smith will be the first to tell you that Smart, ever the motivator, doesn’t get nearly enough credit for the way he works with numbers. The two are a perfect match—and the results verify it.

“The offensive meetings are more fun,” Smith said, “and take a lot less time than the defensive ones.”

There are multiple layers to Marquette’s success over the last three seasons. Smith is quick to defer some of that credit, but there’s no denying he’s played a significant role. Wins help tell the story, but there’s a real sense that his role in Milwaukee is a culmination of his career building blocks—offense, culture, relationships, and schemes—coming together at 12th and Wisconsin St.

“This is the most fun I’ve ever had,” Smith said.

Ask Nevada Smith what his offensive philosophy boils down to, and you’ll get a simple answer.

“You’ve got to dominate the rim,” he says.

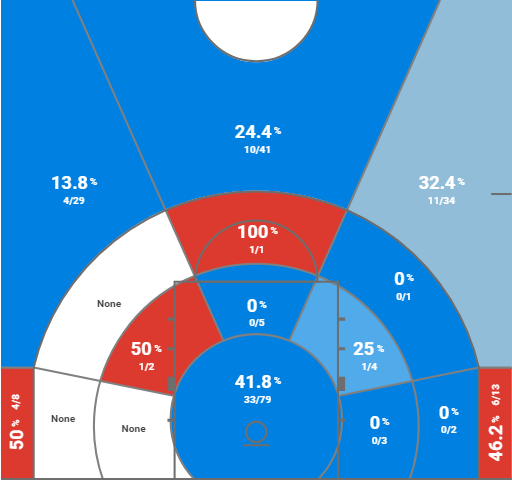

The results of this mindset are evident in the data. In 2019, as Marquette came within a game of a Big East crown under the previous administration, only 26.4% of its shots came at the rim, ranking in the 31st percentile nationally, per CBB Analytics.

This season, the third under Smith’s offensive philosophy, 38.5% of Marquette’s attempts have come at the rim, ranking in the 94th percentile of all Division I teams—a season after finishing in the same 94th percentile.

And while the “threes” component of dunks and threes usually gets more attention, it’s the rim domination that has taken Smart’s offenses to another level alongside Smith. Of Smart’s 15 teams he’s coached, the top 4 in terms of 2-point field goal percentage have come the last four seasons—all with Smith on the bench.

Think of Smith’s offense as five quarterbacks, getting to a spot and making reads based on where the defense has shifted (or, more appropriately, where Marquette’s action has shifted them). Certain spots on the floor have specific actions, with players taught to go through progressions for a shot, pass, or dribble, which begins a new set of reads.

Spacing is crucial to open up driving lanes, and though Smith’s offenses will at times hunt individual defenders to create mismatches, the truth is that if the ball stays moving and players are making correct reads, something will almost always be open. Mid-range shots aren’t bad shots—just lower on the pecking order. There aren’t all that many set plays, which in turn makes it difficult for opposing teams to scout—and Smith is calculated in where specific players are on the floor based on how Marquette wants to attack. Nothing is done by chance.

“So there’s our staff—me, Cody, Neill, Dre, and the rest of the staff—and then Nevada in terms of how he sees the game over here,” Smart said. “And that’s good, it’s really good. I’m so glad we have him.”

He has an unrivaled passion with 2-for-1s at the end of halves, and running in transition is just as much about getting the defense on its heels or into mismatches as it is looking for a quick bucket. Corner 3s are always great, but a dunk, layup, or free-throw attempt will always be the main goal. His logic? The end result is to put the ball in the basket—get as close to it as you can. Easier said than done, of course, but also easier with a dynamite trio in Kolek, Oso Ighodaro, and Kam Jones.

“Obviously we have 11, 13, and 1, which make life easy,” Smith said, “but the creativity that those guys play with probably make it look easier than it is. If you get players that are coachable, teachable, and want to learn, they’ll be good.”

It’s why Smith and the rest of the staff recruit players with great basketball IQs above any other trait. All players want to score—and most of the high school talent Smith and the staff are recruiting are pouring in 20 or more points per game—but there’s a level of buy-in and trust required of the offense given the freestyle and creativity allowed within it.

“It gives you freedom to do certain things,” Kolek said, “but you also have to play within your role and know who are going to be the people that make the plays. He preaches having the ball in the right people’s hands and taking the right shots. It’s all about discipline.”

Smith is stoic on gamedays, always sitting on the first seat closest to the scorer’s table and Smart. He’s rarely animated on the sidelines or in practice, atypical from most college coaches. Perhaps stemming from his NBA days, Smith deploys a calm demeanor—just a tad bit different from Smart—and discussions always have purpose in mind.

“He’s going to tell you how it is and what’s expected of you,” Kolek said. “It’s just maybe not how another coach would have said it or how you would want to hear it. It’s definitely good.”

Smith’s peers laud his basketball mind. They laugh reminiscing about the times they spent together off the court. Every single one of them insists he never played a lick of defense—but you can ask him about his Defensive Player of the Week award at Pittsburgh’s Born 2 Run camp in 1998.

Above all else, those same peers are unendingly happy for Smith. They’re proud of him. They always sensed he was destined for something like this, but that hasn’t made it any less fun or exciting to watch play out. Those same peers aren’t in the rear-view mirror, either. Smith has never forgotten his roots—and there’s a reason why someone like him is excelling at a program whose slogan begins with relationships.

Relationships mean dipping out of a meeting with Spoelstra and Pat Riley to take a call from a friend: “I’m like, ‘Dude, you’re meeting with Spo and Riley?’” Cooper said. “‘Why are you answering me?’ But that’s just who he is.”

Relationships mean hopping on a Zoom call last month to talk offense with Devin Cooper and Keon Price, two point guards playing for Rossi’s Montclair State Red Hawks. “We’re playing New Jersey City University,” Rossi said, “and they’re watching clips against UConn. They’re like, ‘This is awesome!’”

Relationships mean flying to upstate New York to attend funeral services for Jim Mullins’ sister in 2015, four years after Smith left Ithaca: “I never expected Nevada to come up,” a tearful Mullins recalled. “I can’t believe he did that.”

Ten years ago, Nevada Smith was scheming offenses for his 5-foot-9 point guard to cut through Elmira College’s defense. 10 months ago, Smith was cutting down the Big East title nets in Madison Square Garden in front of 20,000 fans. So where will he be 10 years from now?

“Hopefully being a really good Dad to two girls who are in really good shape in life and good people,” he says. “The rest will take care of itself.”

That answer is the essence of Smith.

Smith has since traded out the Mystery Machine for a Ford Explorer, a bit more suitable for the frosty winters of Milwaukee—and for wheeling around his two daughters, Finley and Scotland, and his wife, Lindsay. He’d eventually love to find a spot somewhere in Saratoga Springs, where he spends time in the offseason, getting to simply be dad and husband. It’d also give him an opportunity to make a quick drive to Ithaca or La Plume to see old friends.

What you see is Kolek dribbling off a screen from Ighodaro, who slips toward the rim and receives a perfect bounce pass. Help comes from the corner to double Ighadaro, who recognizes it immediately and finds Jones in the corner for an open 3-pointer. Simple, right?

The truth is that ball movement, chemistry, and production that has awed fans and critics alike is an outcome 20 years in the making. Smith’s core concepts and philosophies have never wavered, but each stop has allowed him to adapt to what and who is in front of him. Though his basketball journey is far from over, the proof is in the results: Marquette’s offensive architect has figured it out.

Wow. What a tremendous, job, Mark.

This (thoroughly researched!) piece was served up to me courtesy of the Google algorithm. And I’m glad it was.

Nevada was probably 13 or so (I was maybe 18) when he began showing up at the West Leechburg, Pennsylvania, schoolyard in his Reggie Miller jersey. (Then, years later, in that van.)

Long story short: Nevada has never lacked confidence : )

I’ve spotted him on the Marquette sideline the past couple years and am happy for his success. Please give him my best if the opportunity arises, and thanks for an enjoyable read.

~ Matt Sober

Incredible story. Thank you Mark.